Ring-billed Gull

The Washington representatives of this family can be split into two groups, or subfamilies. The adaptable gulls are the most familiar. Sociable in all seasons, they are mainly coastal, but a number of species also nest inland. Many—but not all—are found around people. Gulls have highly variable foraging techniques and diets. Terns forage in flight, swooping to catch fish or insects. They dive headfirst into the water for fish. Although they are likely to be near water, they spend less time swimming than gulls.

General Description

A medium-sized, white-headed gull, the Ring-billed Gull appears similar to the Herring and California Gulls, but is smaller, with a shorter bill that has a broad, black ring around it. The Ring-billed Gull is slightly larger and bulkier than the Mew Gull. The white body and tail, slate-gray back and wings, and black wingtips with large, white spots (windows), typical of most gulls, are all present on the Ring-billed Gull. The juvenile is mottled brown mixed with adult plumage characteristics. It has pink legs and a pink bill with a dark tip. As the bird matures, the legs turn yellow, and the bill becomes yellow with a black ring. The adult's eye is also yellow. The adult in non-breeding plumage has brown streaking on its head. The Ring-billed Gull takes three years to reach maturity.

Habitat

Ring-billed Gulls are found in a wide variety of habitats and occur over much of inland North America. They are usually found near fresh or salt water, and take advantage of foraging opportunities in developed areas such as parking lots, restaurants, garbage dumps, and agricultural areas. They also inhabit more natural areas such as coasts and bays. They are rarely found far offshore.

Behavior

Like most gulls, Ring-billed Gulls are gregarious, adaptable, and opportunistic. They do much of their feeding on land, but also forage while wading, swimming, or flying. These gulls spend a considerable amount of time scavenging and often steal food from other birds. They congregate at sewage ponds and in agricultural fields, where they follow plows, picking up insects and small rodents.

Diet

Ring-billed Gulls eat a wide variety of things, including insects, grubs, earthworms, sewage, garbage, small rodents, fish, and other aquatic organisms.

Nesting

The Ring-billed Gull can be found in mixed colonies with larger gulls, where they are often forced to use sub-optimal habitat close to the water, and their nests are at risk of flooding. Colonies are located on low-lying, sandy islands, and nests are built on the ground. Both members of a pair help build a small nest of grass and twigs. Both help incubate the 2-4 eggs for 4 weeks, and both help brood and feed once the young hatch. The young may wander out of the nest after 2 days, but will stay close until after they fledge at about 5 weeks. Nests with more than four eggs are usually the result of two females sharing a nest.

Migration Status

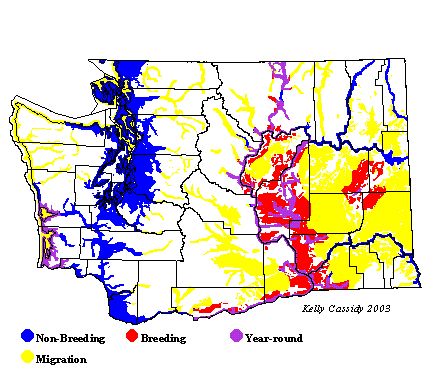

Ring-billed Gulls migrate in flocks, following coastlines and major river valleys. In Washington, many winter residents are present along the coastline. Breeders in eastern Washington may stay in the lowlands year round, but many migrate to the coast.

Conservation Status

The Ring-billed Gull population suffered a major decline at the beginning of the 20th Century because of hunting, but it has since rebounded and is currently thriving throughout its range, so much so that it is considered a nuisance in some areas. Much of the current population boom can be attributed to its ability to exploit food sources such as garbage dumps, large-scale agricultural operations, and irrigation facilities. In 1990, the North American population of Ring-billed Gulls was estimated at 3-4 million and growing. The first breeding colonies in this state were in eastern Washington and were established as early as 1930. Ring-billed Gulls did not colonize western Washington until 1976, when the first pairs nested at Willapa Bay and Whitcomb Island in Grays Harbor. Dam projects in eastern Washington have helped the population continue to grow in that part of the state. The population has grown in western Washington as well, but competition with larger gull species may restrict this growth.

When and Where to Find in Washington

The Ring-billed Gull is common in eastern Washington, breeding colonially on gravel islands in lakes and rivers, and feeding in agricultural fields, cities, and wetlands near the breeding colonies. In western Washington, they are locally common on the dredge-spoil islands in Grays Harbor and Willapa Bay. Non-breeders are also abundant in western Washington in the summer. Migrants have been observed at fairly high elevations in the Cascades. In winter, they are common in coastal areas and the Puget Trough, and are fairly common in eastern Washington in the Columbia Basin, although they are less common here in severe winters.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | U | U | U | F | U | U | U | C | C | U | U | U |

| Puget Trough | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

| North Cascades | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | |||||

| West Cascades | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

| East Cascades | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

| Okanogan | F | F | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | F | F | F |

| Canadian Rockies | F | F | F | C | C | U | U | U | F | F | F | F |

| Blue Mountains | R | R | R | R | R | |||||||

| Columbia Plateau | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Laughing GullLarus atricilla

Laughing GullLarus atricilla Franklin's GullLarus pipixcan

Franklin's GullLarus pipixcan Little GullLarus minutus

Little GullLarus minutus Black-headed GullLarus ridibundus

Black-headed GullLarus ridibundus Bonaparte's GullLarus philadelphia

Bonaparte's GullLarus philadelphia Heermann's GullLarus heermanni

Heermann's GullLarus heermanni Black-tailed GullLarus crassirostris

Black-tailed GullLarus crassirostris Short-billed GullLarus canus

Short-billed GullLarus canus Ring-billed GullLarus delawarensis

Ring-billed GullLarus delawarensis California GullLarus californicus

California GullLarus californicus Herring GullLarus argentatus

Herring GullLarus argentatus Thayer's GullLarus thayeri

Thayer's GullLarus thayeri Iceland GullLarus glaucoides

Iceland GullLarus glaucoides Lesser Black-backed GullLarus fuscus

Lesser Black-backed GullLarus fuscus Slaty-backed GullLarus schistisagus

Slaty-backed GullLarus schistisagus Western GullLarus occidentalis

Western GullLarus occidentalis Glaucous-winged GullLarus glaucescens

Glaucous-winged GullLarus glaucescens Glaucous GullLarus hyperboreus

Glaucous GullLarus hyperboreus Great Black-backed GullLarus marinus

Great Black-backed GullLarus marinus Sabine's GullXema sabini

Sabine's GullXema sabini Black-legged KittiwakeRissa tridactyla

Black-legged KittiwakeRissa tridactyla Red-legged KittiwakeRissa brevirostris

Red-legged KittiwakeRissa brevirostris Ross's GullRhodostethia rosea

Ross's GullRhodostethia rosea Ivory GullPagophila eburnea

Ivory GullPagophila eburnea Least TernSternula antillarum

Least TernSternula antillarum Caspian TernHydroprogne caspia

Caspian TernHydroprogne caspia Black TernChlidonias niger

Black TernChlidonias niger Common TernSterna hirundo

Common TernSterna hirundo Arctic TernSterna paradisaea

Arctic TernSterna paradisaea Forster's TernSterna forsteri

Forster's TernSterna forsteri Elegant TernThalasseus elegans

Elegant TernThalasseus elegans